Self-Care as Self-Preservation: A Deep Dive into the True Meaning of the Trendy Buzzword

Did you know that the term self-care originally meant something more than bubble baths and sheet masks? (Though it can certainly include those things.) Here, a deeper look into what a civil rights activist meant when she first talked about self-care as self-preservation.

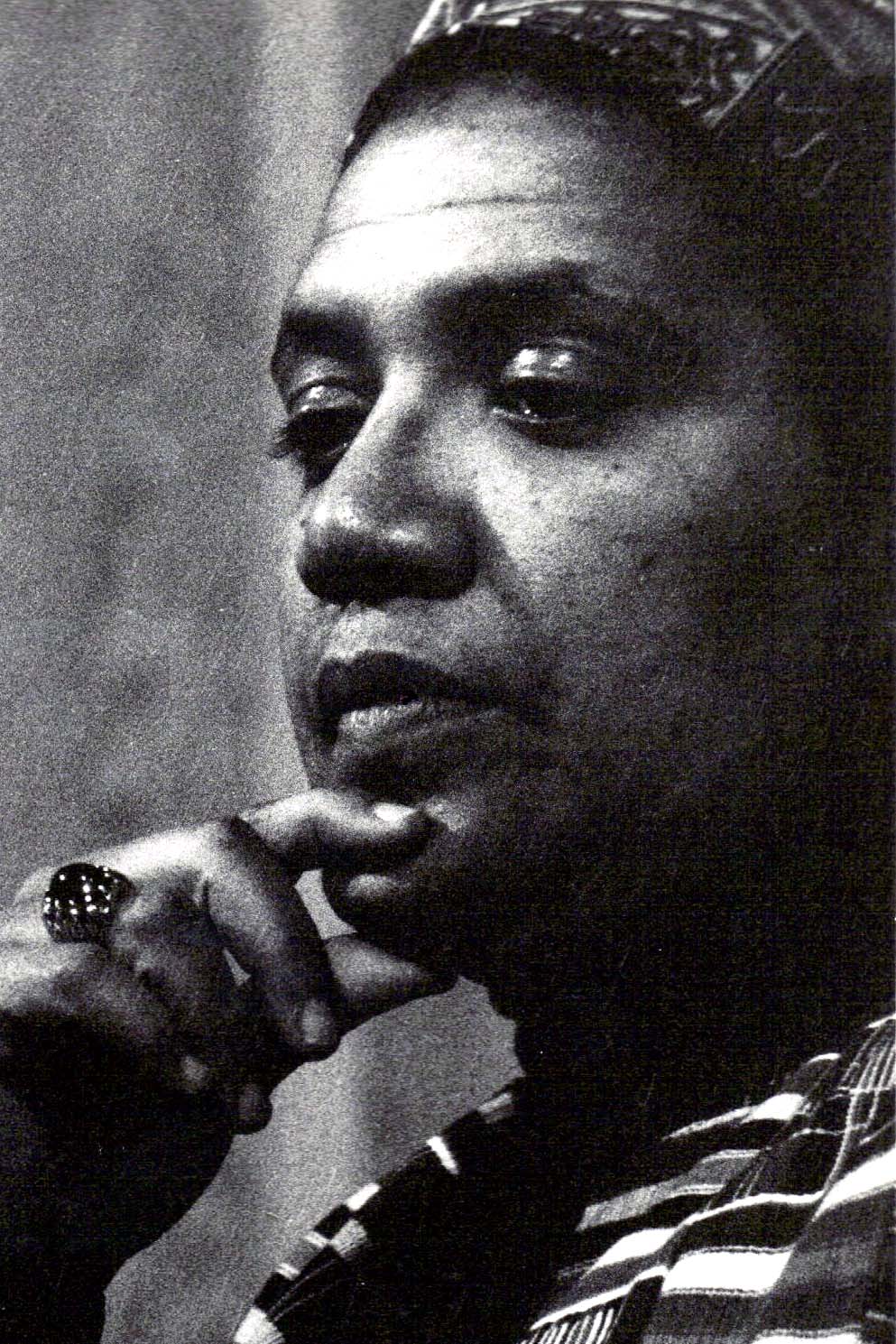

Like most Americans, I run across the term “self-care” mostly in the context of beauty. #Selfcaresaturday, for example, is a delightful hashtag that mostly shows me face and body and bath products. I love sheet masks, obviously, but I know self-care goes deeper than beauty. Audre Lorde wrote this line in her 1988 essay “A Burst of Light”:

“Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.”

She makes two claims here. One — that self-care is self-preservation — is certainly true for me. The other — that self-preservation is an act of political warfare — doesn’t apply to me in the same way, and that affects how I think about what she wrote.

Let’s take a look at the more difficult one first. (Don’t worry, this part is short.)

Self-preservation as political warfare

Audre Lorde was a civil rights activist. She was also a Black feminist lesbian. Not just her work, but her very self was a threat to the powers that be. Her presence, her poetry, her insistent existence as a proud and whole human who would not be silenced were a message of strength to other marginalized people. She was a lighthouse.

When she preserved her self, Audre Lorde was preserving something that threatened the status quo. My trans women friends, who are finally letting themselves revel in beauty practices coded “feminine,” are too. I’m not sure preserving my white cisgender straight-passing self is inherently an act of political warfare.

This doesn’t mean it isn’t worth doing. Maybe political warfare isn’t even your thing. (It does happen to be my thing.) There are other reasons to preserve your self: so you can be whole for your family, so you can be of service to others, or just … so you can be happy. I believe pursuing joy for its own sake is worthwhile. As the famous author said, “Time you enjoy wasting is not wasted time.”

However. Since I am a feminist killjoy, I must suggest that we should be careful about this. By “we” I mean “people who can easily tread on others without meaning to” — highly-educated white ladies like myself, for example. Do I only have the time for a restorative sheet masking session because the nanny took the kids? Who’s supporting the nanny in her off hours so she can preserve her self too?

Self-care as self-preservation

How does caring for my self preserve it? What’s the mechanism? What do we do? This question is less challenging than Lorde’s other claim, and rather more fun to figure out.

I have a friend who prefers the term “self-stewardship.” (Stewardship is “the job of supervising or taking care of something,” according to the Oxford English Dictionary.) By this she means it is our responsibility to manage ourselves, to take care of ourselves as we would a resource like our water or our forests. I like this twist: that rather than making us happy, self-care’s purpose is to preserve our selves — that we may be more whole, more available, or more who we are meant to be.

I’m a science-minded person, so to me the correlation is clear between times in my life when I’ve been healthy and happy and times when I’ve scheduled space to replenish my energy. When I worked absurd hours under intolerable stress, I was a shell. I lost my temper when my students made mistakes. I sat like a lump instead of playing with them. I read books like an automaton rather than like a fun adult. I didn’t cook, garden, or exercise because I was always exhausted. When people asked me what I thought or felt, most of the time I didn’t even know.

What we actually do to care for ourselves is different for each of us. When I’m at the end of my rope I need solitude, peace, heat, and time. Give me a week of rest, and I can recover from a few months of too much work. Give me two hours of rest, and I can prepare for an evening of being with other people. That way, when I return to work or to the world, I have a self to give.

What’s restorative to my husband is time with his friends and a mandolin. I know people who go to rock concerts or who travel overseas. I’m grateful, if I’m honest, that my needs can be met at home without any particular expense. Once after a surprising deep talk with a Lyft driver (these things happen to you too, right?), she gave me this instruction: “After you get out of the car, you’ve got to call your energy back to you.” I sat stunned for a moment. She had it exactly right: I pour out my energy, my self, when I interact with others. If I don’t deliberately take the time to pull myself back together afterward, I stay in pieces for a long time.

Self-care in practice

Here’s what it actually looks like in my life. If go out when I haven’t had enough solitude and spiritual practice or skincare time, I am miserable to be around. I pin on a sort of a rictus “please don’t talk to me” smile and park by the snacks and jump at the slightest noise. I can’t connect with anyone, I can’t listen, I can’t really be a friend. At home I’m also a bit of a nightmare: I freak out about surfaces not being wiped down and cannot cope with any disturbance to my sleep.

Doesn’t living with me sound like a party?

On the other hand, if I go out when I’ve had some deep quiet time first, I can look for someone else wearing a rictus smile and sit next to them. I can ask them about their life, find something that lights them up, and keep us on that topic. At home I can wink at my husband and wipe the counter down myself.

Self-care at its best is me putting on my oxygen mask. This has two purposes. First, so I have enough air to breathe while I put on other people’s masks for them. If I don’t do it I pass out before I can help. (Nearly literally. I used to have all kinds of neuro symptoms when my job was more stressful.) Second, I put on my mask so I have enough air to breathe, period. So I can just sit here on my couch with some pizza and a cup of tea. So I can read a book I’m excited about. So the sleep I get tonight will be enough to get me through tomorrow.

“Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.”

When they talked about self-care, Audre Lorde and other earlier activists weren’t just talking about their happiness. They were talking about their survival and their ability to thrive in a world that is hostile to who they are. I don’t share that experience. The world is mostly not hostile to who I am.

When I talk about self-care, I do mean self-preservation. But I do not pretend that for me, self-care is political warfare.

I want to be a luminous person. I want to be generous, warm, and ready to be of service. I am only those things when I am taking care of myself. And I also think there is something to the idea that any woman’s free-bodied full-throated delight is revolutionary. Some days a good sheet mask feels like a f*-you to some of the people who’ve found me too much: too loud, too androgynous, too opinionated. Check me out, I’m saying. You shushed me and tsked at me and I am here, whole and hydrated, doing what I want no matter what you think.

I do not kid myself that I can pursue delight without paying attention to how that affects others, especially people more oppressed than I. But when I can do it ethically, then why not? Why not sink into what brings me joy? It’s healing, it’s restful, and it’s a celebration that I am still here.

Plus, self-care makes me a better channel of good things to other people. When I’m wearing my oxygen mask I can bring peace and comfort and sometimes a diplomatic skirmish about an important point. (‘Tis the season, you know. The holidays are great times for those diplomatic skirmishes.)

I’m both happier and more useful when I’m whole.

What’s self-care to you? How do you steward your resources, and what do you do best when you’re at full strength?

Loading...